Bit by a tick? Next steps and species to know

08-08-2016

As you savor the great outdoors this summer, protecting yourself from ticks doesn't just spare you an irksome bite - it might also help you dodge a serious health problem, says Purdue University medical entomologist Catherine Hill.

Ticks can carry a wide variety of pathogens, parasites and viruses and can potentially spread diseases to their hosts by regurgitating infected saliva into the feeding wound they create in hosts' skin.

"Ticks have a greater impact on human health that we sometimes give them credit for," Hill said. "They can be powerful vectors of disease."

Indiana is home to several medically important tick species, including the blacklegged or deer tick, which can transmit Lyme disease, the most common vector-borne illness in North America.

Taking steps to prevent tick bites and knowing how to correctly remove a tick if you find one attached are key to avoiding tick-borne diseases, Hill said.

How to prevent tick bites

To help protect yourself from ticks, Hill advised wearing light-colored clothing with long sleeves and pants tucked into socks if you're headed into grassy or wooded areas. You can also use a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-approved repellent or treat your clothing with permethrin. Nevertheless, checking your person and clothing thoroughly for ticks once you go indoors is crucial, Hill said.

"If you can remove a tick within 24 hours, you have a very low chance of acquiring pathogens," she said. "That's why we advise immediate tick checks."

Ticks can wander over the body before selecting a feeding site, and they tend to prefer areas that might seem less obvious such as the head, around the hairline, in the armpit and the groin. Remember that ticks can be tiny - the nymph, or juvenile, blacklegged tick is no bigger than a poppy seed before it has started bloodfeeding.

How to remove a tick

If a tick has anchored into your skin, remove it promptly. Apply a pair of fine-tipped tweezers to the skin, grasp the tick and pull upwards with firm, consistent pressure. The tick will eventually release.

Be careful not to break the tick, which could leave its mouthparts in your skin, potentially causing infection. Using a match to burn the tick, smothering it with mayonnaise or freezing it are ineffective ways of removing ticks and could be harmful, Hill said.

"Doing those things to a tick might encourage it to regurgitate back into the wound," she said. "Ticks are potentially full of bacteria and viruses, and you don't want those pathogens to be introduced into your body. You don't want to squeeze it for the same reason."

Once the tick is out, swab the wound with rubbing alcohol to sterilize it.

Symptoms of tick-borne illnesses

Symptoms of tick-borne diseases can include headache, fever, fatigue, rash, and muscle aches and pains. But reactions can differ widely from person to person, Hill said, and some people could pick up a pathogen without showing symptoms. Skin reactions will also vary. Some people break out in the classic bull's-eye rash associated with Lyme disease or the spotty pink rash that spreads from limbs to trunk associated with Rocky Mountain spotted fever. But others show no such reaction.

"Using a rash is not a good diagnostic," Hill said. "What's important to know is that if you've been out in tick habitat or you've got a tick bite and develop these symptoms within two to 10 days, you should see a doctor and seek immediate medical treatment."

Key species to know

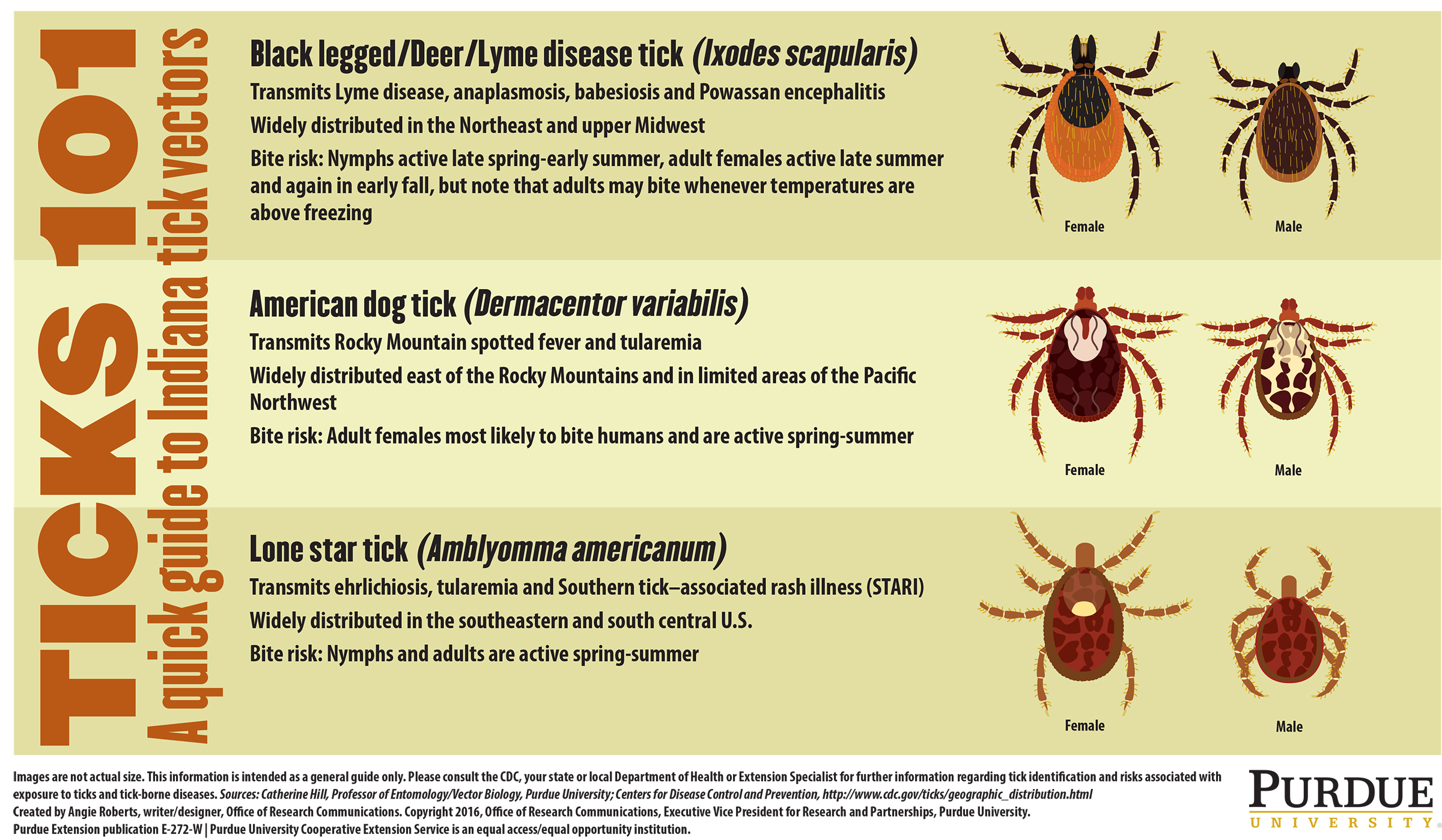

Indiana is home to at least 15 species of ticks, but three are of particular importance to public health, Hill said: the blacklegged, or deer tick, the American dog tick and the Lone Star tick.

Of these, the blacklegged tick is the most significant, Hill said, as it can transmit Lyme disease. While not fatal, Lyme disease can be permanently debilitating if the infection is not treated before it reaches the chronic phase. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed 100 cases of Lyme disease in Indiana in 2014, and a percentage of blacklegged ticks in Indiana sampled by Hill's lab tested positive for the bacteria that cause Lyme.

"We know Lyme is in the Indiana blacklegged tick population," Hill said.

The blacklegged tick can also transmit anaplasmosis, babesiosis and Powassan virus.

The American dog tick can vector Rocky Mountain spotted fever and tularemia. The Lone Star tick - named after the distinct white spot on the female tick's back - can transmit erlichiosis, tularemia and Southern tick-associated rash illness. It could also be linked to an allergic reaction to mammal products, a condition known as alpha-gal allergy.

A free Purdue infographic offers a visual primer on Indiana's medically important tick species and is available through the Purdue Education Store at https://edustore.purdue.edu/item.asp?Item_Number=E-272-W#

Writer: Natalie van Hoose, 765-496-2050, nvanhoos@purdue.edu

Source: Catherine Hill, 765-496-6157, hillca@purdue.edu

Agricultural Communications: (765) 494-2722

Keith Robinson, robins89@purdue.edu

Agriculture News Page